Chen Guangwu produces only calligraphy. His approach is simply the act of writing a word. And repeating it, and then repeating other words similar to it. Simple though his work may appear, there is nothing simple about the art of calligraphy upon which it is based. This is a skill acquired through long and patient hours spent in the company of brush, ink and paper. The act of repeating strokes and forms is integral to mastering the art. Repetition requires patience and discipline. It may allude to Zen meditation, to the rigours of ancient wu shu arts, to accepting order in Confucian learnings, and yet beyond the specifics of any one of these disciplines, the enduring spirit essential to becoming a master seems to come easily to the Chinese people when determination is strong.

While an attribute that Westerners find hard to comprehend at times, it is well illustrated through the history of Chinese art, most obvious in traditional gongbi and fine xieyi paintings, and the laboured brushes of the realists. More modern examples would be the crosses of Ding Yi, and the wide variety of objects that Lin Tianmiao binds with cotton thread.

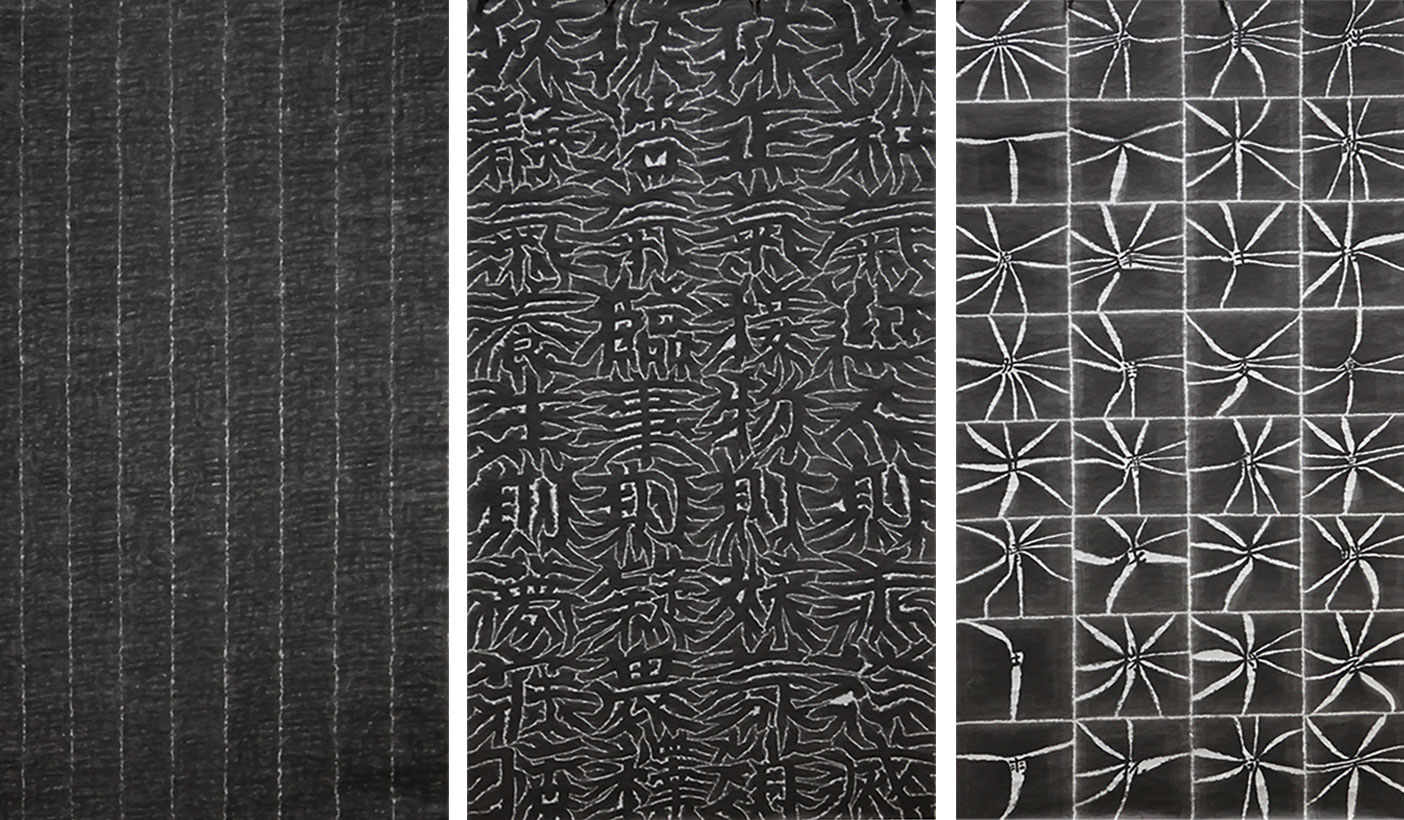

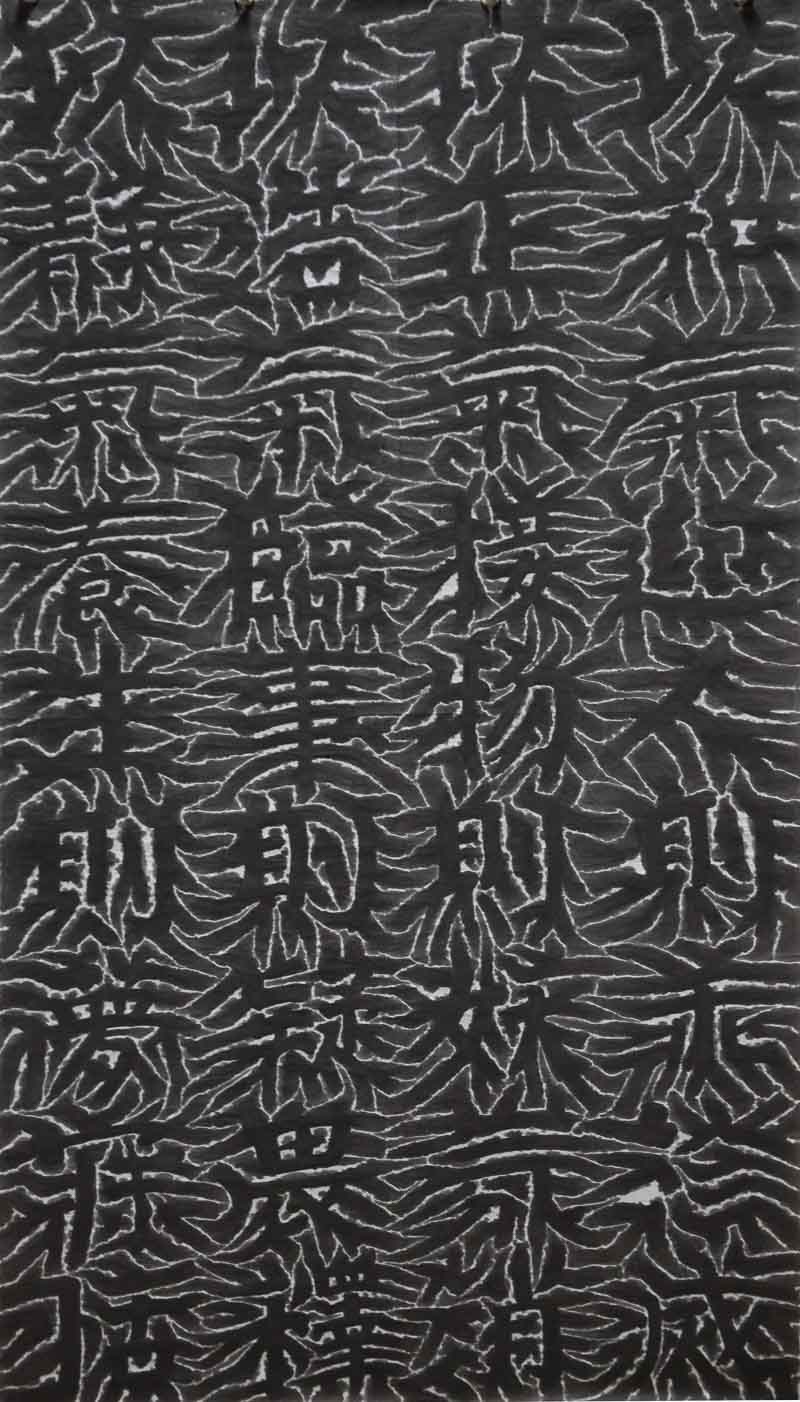

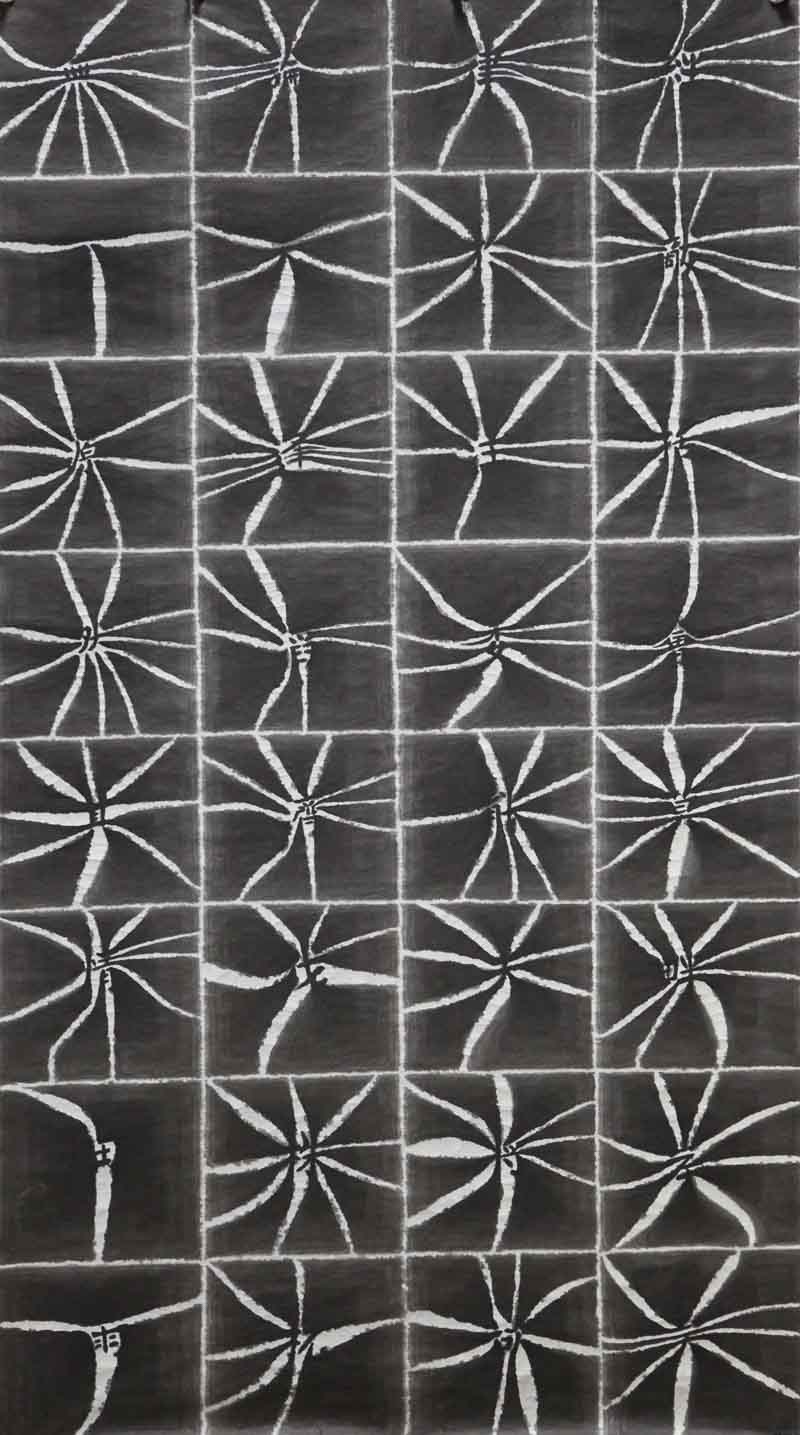

There is a superficial correlation between Chen Guangwu’s calligraphy and Ding Yi’s networks of lines, but where Ding Yi perceives himself as an abstract artist, Chen Guangwu speaks of himself as a pure calligrapher without any link to an abstract agenda. His works are executed in the most traditional sense as he writes the characters, close together on rice paper, layer upon layer. This he does everyday, as from ancient times, all calligraphers would daily write a whole sheet of characters in order to perfect their hand. It is that essential practice that allows words to flow with poetic harmony. Where his work diverges from tradition is not in the close proximity of the characters which appear in rows, bumper to bumper from top to bottom of an uncut sheet of rice paper. The difference is that Chen Guangwu writes layers of words.

Tradition is a difficult word to use precisely; how should it be defined in regard of any art that has evolved over a period of time? Forms, approaches, materials develop with every evolution, making them slightly different from each prior evolutionary stage. Thus what is termed ”tradition” is different at every stage of the game. The “tradition” to which we so readily refer is in reality hundreds of traditions all closely following one another, all of incremental difference yet in our minds they become smoothed together and named as one grand tradition. It is correct to say that in Chen Guangwu’s approach to calligraphy, tradition and modernity are in equal partnership. Here the word tradition can perhaps be used more precisely as an adjective: we can speak of traditional materials, here ink, paper and the brush. These are the foundation of Chen Guangwu’s art. But does the modern style of his compositions negate the traditional aspects of his approach? We might claim the repetition of individual words as another tradition, but how do we justify the patient act of repetition as an approach to making art?

Art without content, without concept or artful composition is surely empty, superficial. The content of Chen Guangwu’s calligraphy is the delicate associations of the characters. The concept is that most fundamental to the Chinese language in the word as visual poetry.

The artful composition is created by the structure of the characters themselves when placed side by side and carefully superimposed one upon the other. Chen Guangwu has been writing calligraphy for more than twelve years. Each character is constructed with the greatest of precision and control. The starting point for each work is a selection of a pleasing range of characters. This may derive from a liking for one particular section of a character such as the renzi pang, or the duo pang. With this radical in mind, Chen Guangwu makes a selection of characters in which it features in the same position. Then, upon a full-size sheet of xuan paper, he starts writing. When the first layer is complete, he returns to the starting point and begins the second character. In this way he builds each composition. The changing potion of each character becomes increasingly dense and vague whilst the favoured radical never changes. The regularity of the repeat generates the air of a block print, of a decorative paper. There are myriad readings that could be intuited in these works; the obscuring of language; the layered meanings of all language; that the meaning of expression is not contained in words alone; that viewers can enjoy the poetry of words as a visual pleasure without having to read any deeper meaning into them at all. Or perhaps as with traditional calligraphy, words can be the springboard to launch thoughts on imaginative wanderings.

Comments