Posted: September 7th, 2017 -

Category: Exhibitions

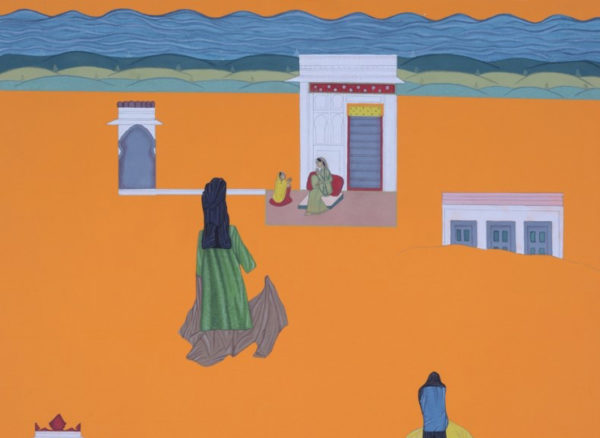

Textiles and Tapestries in the Contemporary Art World

Originally favoured for their portability and ability to both insulate and decorate drafty castles, the tapestry has long been a popular form of textile art. While traditional tapestries still adorn the walls of palaces and stately homes, contemporary versions are increasingly being exhibited. In the National Gallery for example, a large-scale tapestry by Chris Ofilli is currently mesmerising visitors, striking the eye in a very different way to painting. Thanks to a creative process deemed ‘Weaving Magic’, involving five weavers from the Dovecot Tapestry Studio in Edinburgh, each thread is visible in minute detail.

Over at the Whitechapel Gallery, South African artist William Kentridge presents woven silhouettes of figures that parade along stretches of stitched map, and are integrated into a flip-book film inspired by the Shoshtakovich opera ‘The Nose’.

Grayson Perry is famous for his digitally woven tapestries, which although not realised through the blood sweat and tears of hand weavers, demonstrate the synthesis of this traditional medium with rapidly developing technology. The works exemplify the vogue for digitally manipulated art, and whereas tapestries once portrayed fair ladies and unicorns, Perry’s works feature contemporary images such as a smashed iPhone and Hello magazine.

Henry Hussey, a young British artist who creates works which, although they utilise soft fabrics, contain raw and deeply emotional content, believes there is a prominent differentiation between the two subsets of tapestry: ‘It’s worth making the distinction of approach, as weaving by hand is an entirely different process to digitally. It requires the artist to collaborate with the weaver to communicate marks and essentially recreate the works from scratch to capture the essence of the piece,’ he says.

Hussey has worked with the medium of tapestry for several years now, and believes the rise in its popularity may be a reflection of the uncertain times in which we live. ‘It’s a relevant medium to return to this during such a turbulent era and gives precedence to these fleeting moments of despondency and upheaval for future generations to witness’. Tapestry, he believes, also ‘draws attention to materiality’, and allows us to contemplate tangible elements of work, rather than prioritise a concern with the conceptual.

For Hussey, it’s vital that there is a relationship between the material and how it informs our psychology. ‘With textiles or any gestural and sculptural medium we continue to thrive and confirm our existence as something that is able to be expressed’, he says.

Alongside the higher profile of tapestry is a trend for artists to employ textiles in general, using soft fabrics to ask complicated questions and bringing textile art out of its domestic ‘craft’ pigeonhole.

Liza Campbell uses the ‘subdued’ medium of textiles to write harsh and controversial statements, often on interior designs. Her ‘Subversive Sewing’ series features cushions that scream offensive words at their reader such as ‘Freak’ and ‘Motherfucker’’, while sewed samplers show dark twists on the traditional ‘Monday’s Child’ poem. A lace handkerchief embroidered with a dandelion, often associated with daintiness, boldly claims ‘I’m gonna blow your mind’.

Feminist artist Jess de Wahls notes that the medium may still retain ties with its former reputation, with earlier feminist artists in the 1970s using it to prove political points. In her own work, however, she feels the medium has been doubly reclaimed, believing that ‘textile art is very much equal to other visual art-forms, and by singling it out for being a particularly female skill, we perpetuate the myth of the ‘crafty woman.’’

In recent years, artists have attempted to shake off prejudicial notions, and raise the status of textile art. As de Wahls says: ‘It’s a patriarchal construct that I try to break down, simply by refusing to see it as anything less than fine art.’

Certainly there has been a huge shift in the democratisation of textile art, and it is now widely used by male, female, emerging and established artists. De Wahls concludes: ‘The tide is very much turning and we are seeing more and more textile artists welcomed into the “fine art community”. It’s long overdue I’ll say.’

Hussey, de Wahls’ and Campbell’s work can be viewed on Instagram: @henryhusseyartist, @jessdewahls, @lizacampbell24

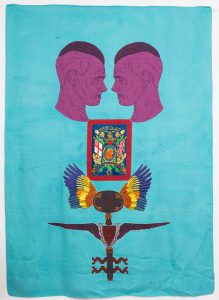

Cover image: (c) ‘Big Swinging Ovaries’ by Jess de Wahls

Comments