Posted: February 3rd, 2016 -

REVIVING TRADITION – PAKISTAN’S CONTEMPORARY MINIATURE ART

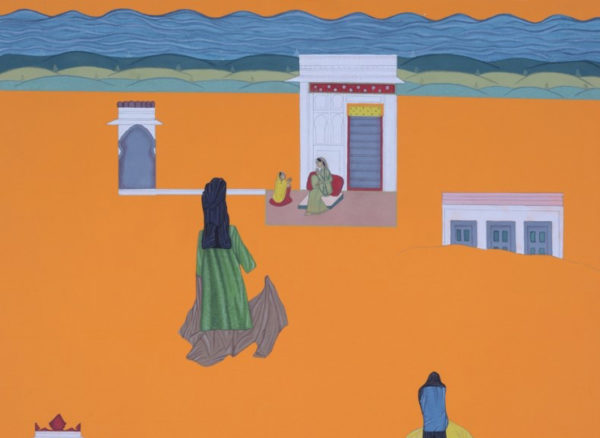

Traditional Miniature painting (title photo) traces its lineage to Mughal India, Iran and Turkey and continues to be practised there today but it has evolved into a new genre in Pakistan with its own identity and aesthetics. Known as contemporary miniature painting or neo-miniature, this relatively new art form is fast gaining recognition and popularity in the international art arena.

Originally considered a craft, miniature painting has been taught in Pakistan’s oldest art school, the National College of Arts (NCA), since 1945. Today the college, which was founded as the Mayo School of Art in 1875 by Rudyard Kipling’s father, Lockwood Kipling, has a miniature painting department and offers it as a major in its Fine Arts degree program. Miniature painting is now also part of the art curriculum in many art schools across the country.

The traditional art form was taught at the NCA by trained court painters. Today the instructors are mainly ex students but students still go through the rigorous discipline of preparing materials (paper, pigments and brushes) and copying original works as part of their training. They are taught to prepare their own wasli paper which is made from gluing together 4 sheets of water colour paper with a special flour and water paste (laee) and polishing the resulting paper with a stone or shell until it is shiny and smooth. While traditionally paints were derived from natural pigments and organic sources, today most artists use ready-made chemical colours. Students also learn the miniature tradition of making a brush from the hair of a squirrel’s tail which is inserted into a pigeon quill and then attached to a bamboo or reed handle. The miniaturist works using his hand as a palette and individual colours are mixed and held in mussel shells which can be easily held between the thumb and index finger rather than in a tray. Rather than sitting on stools, students work sitting on the floor holding their wasli on a low board or on their bent knee which serves as an easel.

The miniature technique is a laborious and precise one. Students must first perfect drawing lines in black ink with a single-strand squirrel hair brush before they can move on. Once they have mastered this they learn rungamezi or filling in the colours. All this is done in minute feather light strokes known as pardokht – a technique similar to pointillism but requiring much more finesse and control and probably the most important aesthetic of miniature painting. Students learn by copying original works from the Mughal era but in their last year they must produce their own original work using the techniques learnt.

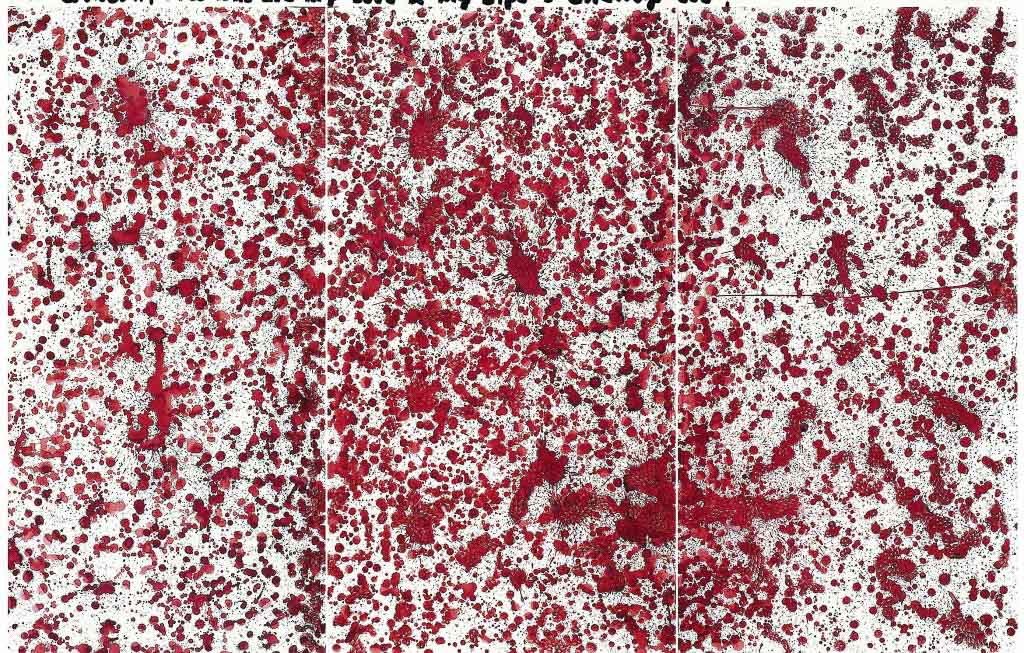

The contemporary twist to miniature painting was initiated by the artist and educator Zahoor-ul-Akhlaq in the 1970s. Having studied at the Royal College of Arts in London and seen miniature works at the Victoria & Albert Museum in London, he proposed a new aesthetic in miniature painting which involved blending the traditional art with western and postmodern materials and innovations. His approach resonated with many of the students he taught. It also addressed the criticism of the old tradition in that it allowed the artists to express their individuality and creativity and was not simply a copy reproduction of historical works. But it was not until 1992 that the current trend in contemporary miniature really took off. One of NCA’s miniature art students, Shazia Sikander, produced a thesis work that combined elements of miniature with a contemporary theme. Not only did her work have a personal narrative, its scale (at 5 feet long) was an outright contradiction of the miniature tradition. Since then, many students at the NCA have followed Sikander’s footsteps with works addressing a wide range of contemporary subjects and themes; from local and international politics to socio-economic concerns like honor killing and the onslaught of media and popular culture. For example, Imran Qureishi’s abstract triptych You Are My Love And My Life’s Enemy Too, 2010 (Fig.1) investigates the country’s socio-political situation via traditional miniature technique and medium but on a larger scale (216 x 366 cm). The wasli paper is covered in what look like violent splatters of blood but up close some of the larger stains and pools of blood bloom into intricately painted flowers. Inspired by a bomb blast in a familiar marketplace in the artist’s hometown of Lahore, opposing themes of violence and nostalgia are depicted in Qureishi’s work perhaps hinting at the hope that there will be a reversal in the troubled fortunes of the country.

Many artists work through subverting the traditional technique as in the case of Muhammed Zeeshan, whose series Dying Miniature, 2009 (Fig.2) critiques the contemporary practice on both formal and conceptual levels. The smooth wasli paper is replaced by rough sandpaper and instead of natural pigments applied by brush to build up layers of detailed images, graphite pencils have been used to engrave the surface of the sandpaper to create jeweled silhouettes of people and animals tied historically to the miniature tradition. This subversion through a reversal of the miniature technique critiques the development of miniature painting in Pakistan over the last two decades and its evolution into the contemporary form popular today.

Artists also experiment with non-traditional media like Rashid Rana whose work Red Carpet IV, 2007, (Fig.3) uses photography and computer technology to create what at first glance looks like a digital image of a brilliant Persian carpet. On closer examination, however, it turns out to be a collage of thousands of pictures of a slaughterhouse. Rana’s work illustrates how behind beauty can be brutality and that what appears to be may be an illusion in reality.

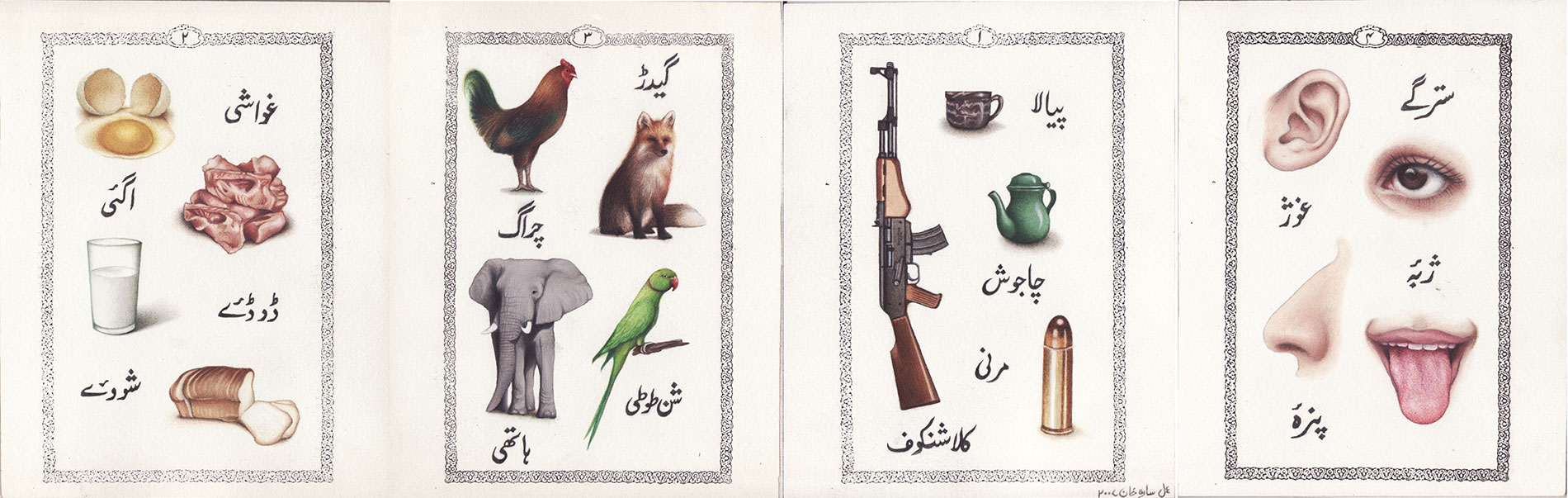

Narratives of personal histories and exploration of their own identities have found their way into neo-miniature too. Sara Khan’s Qaida, 2007 (Fig 4) is a four panel series which investigates her own anxieties and fears about her Pathan ancestry which stemmed from her unfamiliarity with her native language, Pashto. She tackled this by embarking on a journey of learning the language which brought her closer to her roots. Her work done in traditional miniature size and style, takes the form of the pages of a Qaida or beginner’s guidebook which teaches sounds and words through illustrations.

Pakistan’s contemporary miniature art has been widely exhibited on the international art platform via museums and biennales. Its success in the art market has further fuelled its popularity at home. Artists, art critics and historians continue to debate whether contemporary miniature art is really a part of the historic tradition or a reinvention made necessary by the present times. Salima Hashmi, a well known Pakistani artist, writer and curator holds the view that contemporary miniature is not really a celebration of tradition but is using tradition as a springboard for doing something that runs counter to tradition.

In purpose at least, miniature painting remains the same whether it is traditional or contemporary. In centuries past, emperors and rulers of the Ottoman, Persian and Moghul empires commissioned artisans to illustrate books that documented their lives and reign. The contemporary miniature artist, in the current context, does the same – through his themes, and the combination of traditional and modern techniques and media. What they do differ in is independence. The artisan of the past was commissioned and his work represented the view of his patron. Today’s artist has more freedom in his expression: to depict and express the world he lives in as he or she sees it.

Comments