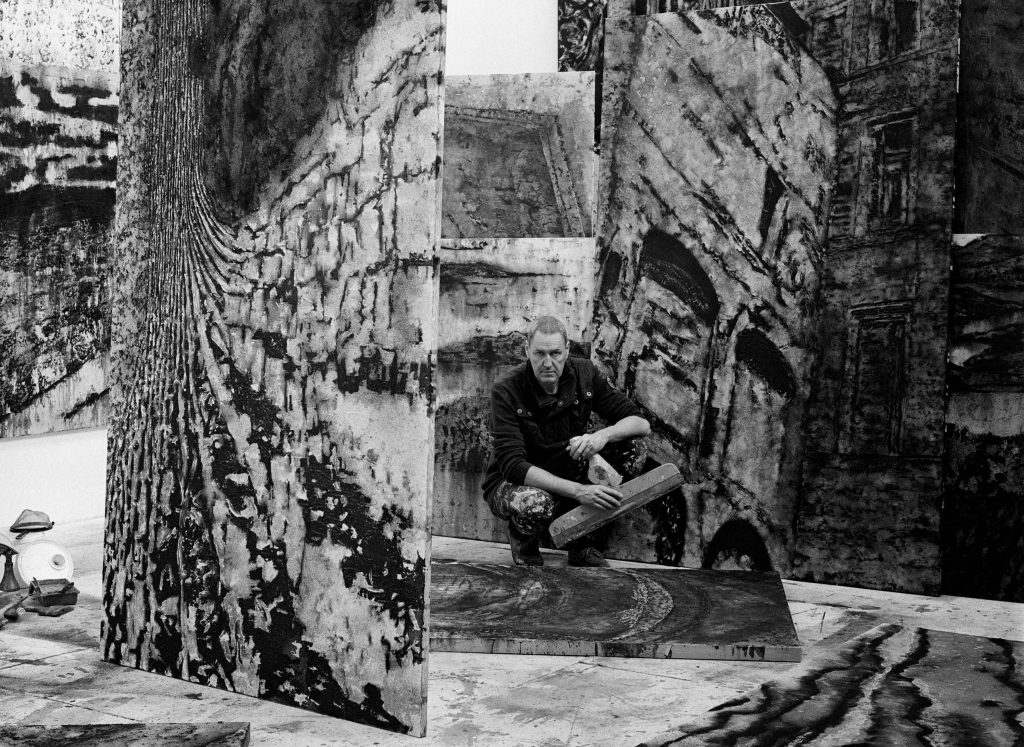

Did you always know you wanted to be an artist?

I never asked myself if I wanted to be an artist. When I was young I was consumed by creative ideas and would constantly draw whatever came into my head. Finally at the age of 11, I had a “physical shock”standing in front of the soft textured oils of Georges Braque I suddenly had the desire to paint and to be in contact with this rich material. After that I suppose I became an artist, though I would not have defined myself as on t the time.

My studies began with an artistic maturity (Baccalauréat) and then I went on to the University of Geneva, to study art history. I then took a workshop at the ESAV (Ecole Superieure des Arts Visuels, present HEAD), where I was then invited to study. At the School of Art I created a portfolio that I then presented to the ECAL where I later went on to win the a painting prize in 1989.

You paint only with natural materials and not with artificial paint – what is your reasoning behind this?

Of the artificial colours available to buy, I never found the materiality and the texture that I was looking for. My blacks were never really black, they lacked density and thickness. So I began to use elements discovered in nature and natural pigments that corresponded to my conception of matter. They are part of my pictorial identity. I paint with the very materials of my themes, materials from the history of mankind. I harvested volcanic rocks that are three billion years old and marine sediments with fossils from 40 to 65 million years ago. When I paint, the materials that I have collected during my travels, find their place. I constantly learn from experimentation, finding success within failure.

AVAILABLE WORKS BY BERNARD GARO

For me, it’s very important that a painting speaks for itself. Viewers frequently ask to touch my paintings, exploring the soft and natural textures. My work goes beyond painting and refers to the ideas of Gilles Deleuze who says that “all arts come together when they are ‘deterritorialised’”, essentially my works are underpinned by emotion. A work begins to gain meaning when one manages to forget the technique and the aesthetic. It is my goal that the spectator witnesses the moment and enters into a state that opens their eyes to a new understanding of the world. It is not a representation, but a structure, a skin, a bark bearing history and memory.

What made you abandon your paintbrush? What do you prefer to work with?

I never use the brush. I abandoned it for the trowel of the builder and the sieve of the baker. I also gave up prepared industrial paint tubes and pigments. For me, colour is what occurs naturally in the materials I collect and use: sand, earth, calcined wood, crushed brick, marble powder, bitumen, silt or latex.

My colours and my canvases fashioned by such utensils refer to the patina of the old stones of ancient monuments, the dark basaltic magmas of the earths crust, the reflections of the Byzantine golds, the flows of volcanic lava, the dusty powder of the deserts and the hard mirrors of the Atlantic ocean.

Whilst your works appear abstract, they do contain varied forms. Do you paint from life when depicting?

I examine the “skin” of the world. I take its pulse and record its movements; I probe at its fragile depths. I observe civilisations and humanity. I question both the vestiges of the past and the beginnings of the future.

My forms are no more forms than traces and structures, thrusts, impulses and ruptures than eruptions and craters, crests and subterranean faults of luminous gaps and dark shadows. You can find elements of nature and architectural fragments that seem to emerge and disintegrate before your eyes. Pieces of ghostly cities haunted by their past splendour and geologically fragile from ancient earthquakes. My formats are mostly monumental, embracing entire continents, vast outer territories but also immense cities where one can get lost.

In what era, what period, what temporality do we plunge into these visions of a world magnified and bruised by the ages, natural disasters as well as destructive genius of men? A mythical time that imbricates and confuses the front, the now and the after. I always paint on the floor to be fully immersed in my work. I avoid great gestures and virtuosity. I mash furious magmas. I allow myself to overflow, sometimes overwhelm, and proceed by strata and sediments; by waves and energies; by vibrations, tensions and force fields.

My painting is tumultuous, a battle, always delivered in a state of emergency. Nothing is ever fixed, finished or petrified. Between anxiety and jubilation, it sustains a fundamental instability which reminds us that everything is always in the process of metamorphosis, disappearance and re-emergence.

What is your personal relationship with architecture?

Architecture is very important to me. On this subject I want to tell you the story of Aphrodisias in Turkey, where I developed an admiration for the subtlety and aerial aspect of a monumental gate with sixteen columns. Later, I took the opportunity to recompose it and reinvent it pictorially with asphalt, latex, the white and pink marble powder of the region and the marine sediments, giving the impression that it could collapse at any time. Seeing this painting in my studio, Michel Fuchs, professor of archeology at the University of Lausanne who specialises in Turkey immediately exclaimed: “But this is the tetrapylon of Aphrodisias!” From his first viewing he recognised the structure of this magnificent edifice and the special spirit of the place, even though I had removed all descriptive elements and deliberately kept only the bone and the breath of the emptiness that surrounds it. He then explained to me that Aphrodisias was a city dedicated to the cult of Aphrodite, and that in Asia Minor, during the Roman period, it was also a great centre of pilgrimage for its school of philosophy, but even more so for its large sculpture school that took advantage of the many high-quality marble quarries located nearby. The artists received orders from all over the Mediterranean basin. They were so renowned that, unlike most of the sculptors of the time who conformed to the defined canons and remained anonymous, they created works with an original style. In the 4th century a violent earthquake caused the city to flood and devastated it. I did not know everything about the richness of this site, but what had impressed me were the traces of the trembling that had ravaged the site. Which means that, in an intuitive way, I had guessed the magic and fragile dimension of this site. This kind of convergent discovery completes me. It adds to my contemplations and stimulates me to go even further in my visual and plastic exploration of the world.

I like architecture the sand, crushed brick, marble powder, tar (still used today to insulate the foundations of houses as 5000 years BC in Mesopotamia to insulate the roofs), bitumen from Judea, lands, silt, fragments of rocks. I also have a love for ruins, decomposition, fragments, entrails, carcasses, the vestiges of buildings: all this touches me deeply and speaks to me of an invisible history. I practice a form of surgery – architectural dissection. I like to understand the relationship of the building to its place, the intentions of the architects in their way to integrate the site and its geology.

What else inspires your work?

I paint in plates and sediments, just like the process of geology. It is something that has gradually been imposed on me, through the techniques that I invented. I like to try to think of the planet in the manner of geologists who apprehend it by the yardstick of geological temporality. It is frightening and beautiful to know that our land is in perpetual motion. It is a notion that I want to show in my painting, but curiously it disturbs and destabilises me. I do not want to give lessons to anyone, I just suggest tools to look at things differently, from a broad and enlightening perspective.

Dance, for example, has a lot to do with my work, especially through my performances and other disciplines like music, because I often collaborate with artists from other fields of artistic expression.

For me, dance is the extension of painting and sculpture. I am first and foremost a painter but I do not like being so resolutely categorised. I need to constantly explore new fields of expression. However, I am not a dancer or sculptor. I am not willing to interfere in areas where my colleagues and friends excel. What I like most of all is to collaborate with them and work out of my comfort zone, that’s always an adventure. The Franco-Japanese dancer Satchie Noro or the musician Eric Fischer as well as the dramatic artist François Chattot are special and faithful partners who enrich my work. The worst thing for an artist is to settle into a system. We must always find new energies and new knowledge through comparisons, confrontations, critical exchanges, risk-taking and failures that push us to renew itself. It’s not just a practice, it’s a choice, a way of life, a necessity!

How has your work changed or developed over the years?

At the beginning I painted in acrylic, conventionally, like everyone else. I had a palette that was shimmering and light. I did not have the means to pay for large quantities of paint, so I developed my own glazes. Despite being influenced by certain masters and professors, I felt the need to find myself. It took me almost ten years after my studies to finally find my own identity around the concept of cities; a concept which itself evolves over the course of projects.

It was in Barcelona where my great passion for Spain developed, from Velasquez to Tapiès, Saura, Barceló and many others. Following my year living in Southern Europe I began looking to constantly balance opposites, contraries and paradoxes. To take the opposite direction took me to Berlin, bubbling with life, energies and metamorphoses. The move between the two metropolises at the turn of the 21st century greatly stimulated me and my work, but I cannot help feeling like a man from south to north and a man from north to south. After all, Switzerland, where I was born, embodies well this north-south axis and derives its wealth from the encounter and confrontation of the two. Between Barcelona and Berlin, my hometown of Basel is almost exactly half way and symbolises the rigour that gives my works their constructive and mental structure. My first great pictorial cycle aligns these three emblematic cities starting with B.

A later project also concerns cities, but through a topography very different from the first it featured: Alexandria, Reykjavík, Lisbon and Istanbul. The project is entitled ARIL.

After focusing on urban centres, I found myself preoccupied with the outskirts. Launched in 2004, the long-term cycle spanned more than a decade and featured around four cardinal points that point to the horizons of a new elective geography. These cities are all located on a circumference marked with a compass whose point would be planted in the heart of the Alpine arc at the summit of the Matterhorn. Consisting of rocks from the African plate, this summit has become a universally popular icon of the Alpine chain and remains hostile and wild. For me it remains the spectacular representation of a subduction zone that engulfed an entire ocean a few million years ago.

The four destinations defined around this symbolic marker are all located equidistance from the “country-city” that is Switzerland. They appear as four gates of the European continent. They are all located in unstable land-based areas, seismic faults, ocean fronts and other volcanic lands that have experienced major natural disasters and are in the front line for new ones.

This impressive project is artistic, of course, but also geographical, geological, historical, societal and philosophical.

The journey ended in spring 2016 with a monumental pictorial installation on the Matterhorn theme, which also generated a test film. My painting is entirely a quest for meaning and knowledge, a constructor of memory, a place of fundamental and existential questions.

The theme of the passage of time and ruins, often associated with that of nature, is one of the important themes in the corpus of works. Recently, I started a new series of ruins which will be the subject of specific publications and projects. These paintings, entitled Ruins Barbares, so far unpublished, express in particular the effects of human self-destruction.

Bernard Garo’s work is available on ArtAndOnly

Comments