Born in Rome in 1978, Ruffo continues to live and work in Italy’s cultural capital. After studying Architecture at the University of Rome, Ruffo was selected for a research fellowship at The Italian Academy for advanced studies in America, (Columbia University, New York), in 2010. Working in a variety of different media including intricate drawing and sculptural works, Ruffo’s practice is meticulously manual. His interests in philosophical notions of freedom and political ideologies are intrinsic to his engagement with his craft, reflecting his intense social and moral concerns and his passionate stance on ethics. He perceives his work as being in a constant state of process-based research, leaving pieces open for viewers to read into the deeper implications behind them. His debut exhibition with Blain|Southern (2012) consisted of a series of large-scale, intricate drawings that explored the concepts of freedom, presented by a number of American moral and political philosophers, creating a satirical optical illusion with raised passages taken directly from influential texts. In 2009 he won the Premio Cairo Award (Italy) and in 2010 was awarded the New York Prize, bestowed by the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs. His work is held in several public and private collections, including Deutsche Bank Foundation, New York, IL, M.A.M.B.O Museo d’arte moderna di Bologna and MAXXI Museum in Rome.

Your work often deals with political and philosophical ideas of freedom. What does “freedom” mean to you?

The concept of Freedom is universal, but so unique to each of us that it intrigues me. After studying the teachings of Isaiah Berlin, I created a project in 2010 called “Six enemies of human freedom”: six lessons that Berlin had given on BBC radio in 1952 on six philosophers of the French Revolution, and how their theories, (though based on sound principles) had become inspirational to authoritarian regimes in the twentieth century. Berlin then, with his ‘two concepts of freedom’, provides an interesting theory on the division of the two blocks during the Cold War period.

After further investigation into the term ‘Freedom’ and with my own understanding of it, I decided to write a research project for Columbia University in New York on similar Liberal American philosophers.

Tell us about how your academic studies in New York have had an impact on your work. Do you continue to study and incorporate philosophy in this way?

In 2010 I spent a semester as a researcher at The Italian Academy of Colombia University in New York. This period was crucial for me in fully understanding how the concept of Freedom in the United States was historically rooted and defined as opposed to the concept of slavery. You are free if you are not a slave, therein you are free from a ‘master’ or an authoritarian state, this is a concept known as ‘individual freedom’.

This is something very different from the concept that accompanies the history of European philosophy, where the idea of freedom is intrinsic to the nature of man. It’s not something that somebody gives you and that you are, you must cultivate together with the people around you in order to create a free society (collective freedom). For what is my freedom if the person next to me is not free?

In New York, I had the opportunity to conduct different interviews with people from all over the world and understand how the concept of freedom is still a geographic concept, completely different depending on the country you grew up in.

How has the current political climate affected your thinking as an artist?

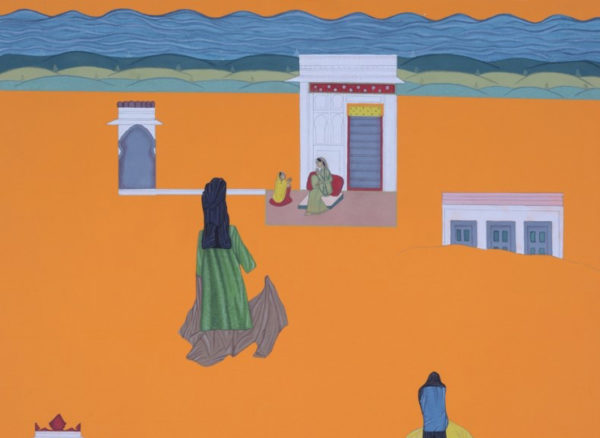

During the last year of such worldwide political upheaval I have been working on a project looking at migration with a historical perspective. The project reflects on the fact that the current political upheavals and instability our governments are facing is in reality the true engine of our shared history.

The delicacy of your paper extractions, the way you cut the paper on which you work, creates a fragility that provides a stark contrast to the images of strength and power that your work portrays. To what extent do you see your work as playing with notions of power and weakness?

The dichotomy between the fragility of the paper material and the power of the message that the work expresses, creates a great deal of force. This notion can take the form of a religious text, an act of war or a peace treaty. This is why I also create war machines, such as a World War II tanker or a World War I airplane; even though these machines still exist, the material used evokes childhood games, which emphasises the fragility of conflict.

Tell us a bit about your choice of medium. Why paper?

The use of paper comes from my training as an architect. When you start a project, the first thing you do is look at the planimetry and aerial photogrammetry of the site that will house your project. The map of the area can tell you many things including who has drawn it, the commissioner of the drawing, and the historical period in which it was created. In my work, I look at the world through maps, through the eyes of geographers of different times. By analysing these maps I can understand a lot about history, conflict and the relationship between people.

Colour often plays a pivotal role in your work, most notably in your ‘Atlases’ series. Where does this interest in colour psychology come from?

My grandfather was a great teacher of art and was a theorist of colour, and, in 1978, introduced his new chromatic circle. This was the first time that this had been done, revolutionising theories of colour from Newton onwards. Colour has therefore always been an important aspect of my training as an artist. In my Atlas series for instance, I took statistical research linking colour and emotion between different people.

By raising your cut out drawings above the surface of your work, you create optical illusions where the boundaries between two dimensional drawings and three dimensional objects are called into question. Tell us a bit about your decision to do this.

My works are made up of a lot of different layers of design and carvings. In every work there are always different stories that overlap. I think this idea of stratification comes very much from the city where I was born and raised, Rome.

Rome is a town where the materials and symbols of previous centuries merge and regenerate continuously, each building is composed of layers of history. Each building speaks to multiple senses on different levels, just as my artwork aims to do.

How do your studies in architecture affect your artistic style?

My art practice is organised as architecture studios were, with several people each working on a specific task, all working on several projects at the same time. I love to work in a group where everyone brings something personal to a project, we share the birth of each piece.

What was the experience of working on the Piazza Mignanelli like? Were there any difficulties when working on such a large scale piece?

The creation of the scenery at Piazza Mignanelli for the 2015 Valentino parade was an incredible experience. It was like being one-centimetre tall and walking within a carved world of scenery with many levels inside. I’ve rarely experienced such a thrill as something that involved more than 100 people working on the site. It was a colossal installation which kept me awake for more than six months and when the parade started lasted only 15 minutes.

© images: Pietroruffo

Artist’s website: http://www.pietroruffo.com/

Comments